At the Uncertainty Project, we highlight models and techniques for strategic decision making that are either thought-provoking, applicable, or both!

Every week we package up our learnings and share them with this newsletter as we build the Uncertainty Project.

In case you missed it, last week we talked about whether or not OKRs are improving or inhibiting decision making. This was the prequel to this week’s post, so it’s worth checking out!

Did you just join us and want to get caught up? Check out this post to get caught up or take a look at all of our previous posts!

This week:

🔮 Today’s Topic: ‘Are OKRs improving or inhibiting decision making’:

Part 1:

Setting the stage - surfacing problems with OKRs and decision making(link)Part 2: Do OKRs hinder decision making in radically uncertain environments? (👈 You are here)

🛠️ New Technique: Shared Visions - Vision statements influence strategy processes. Done correctly, they tap intrinsic motivation, while poorly crafted visions can lead to organizational skepticism.

Last week we asked the question - is there a downside to goal-setting? This week we’ll walk through a few provocative arguments.

I’m personally an advocate for OKRs - they decentralize the agency to identify solutions that produce desired outcomes, but we shouldn’t forget that the goal itself is a choice and a constraint. This is of course a feature, not a bug, but we can’t ignore that the constraint has a profound impact on our decision making.

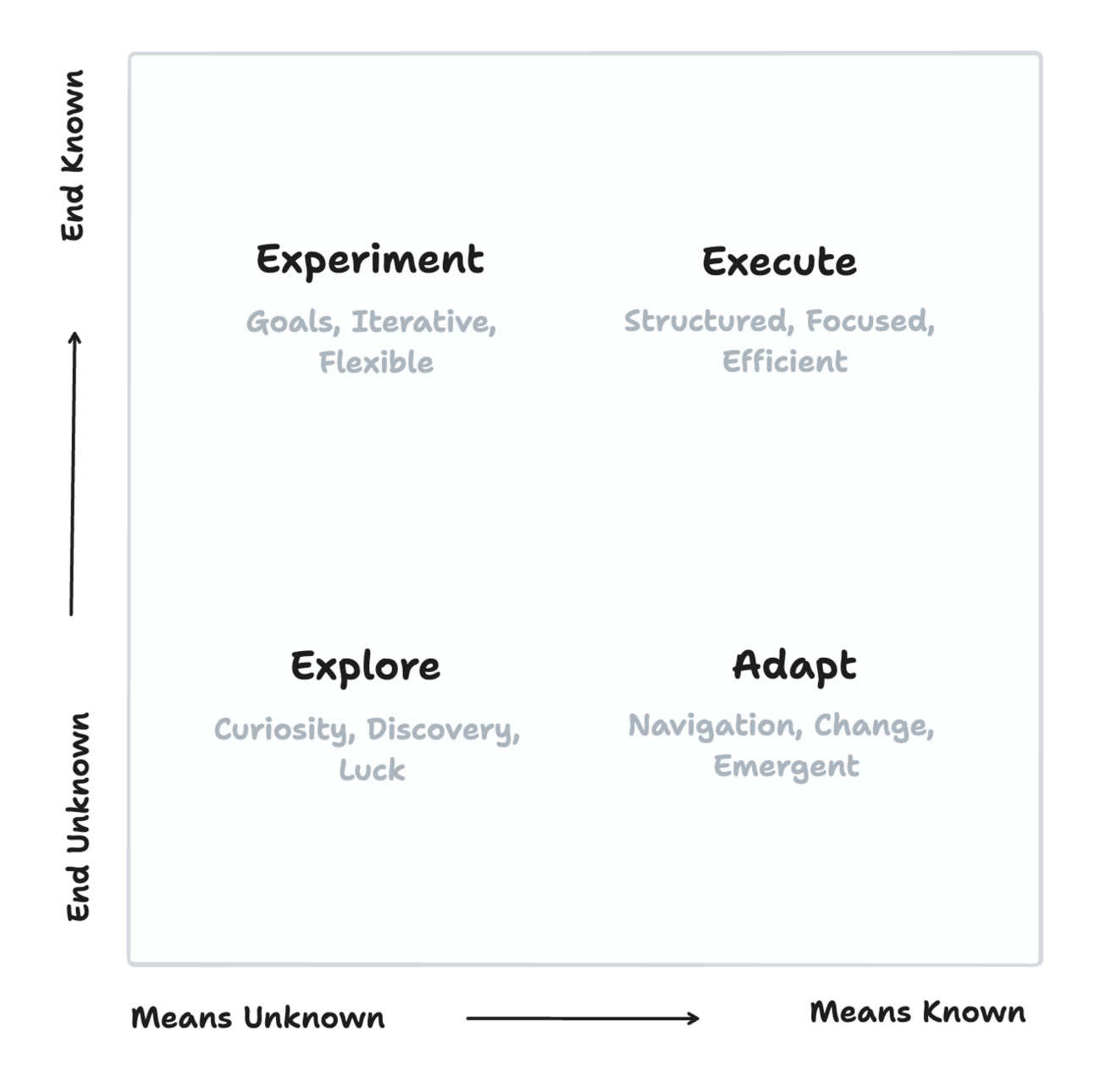

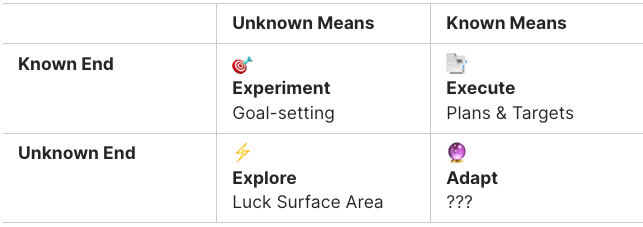

The choice of ‘what the goal should be’ and ‘how to measure it’ boxes us into a ‘Known End, Unknown Means’ scenario. This means we know the desired outcome or change in behavior (the end), but the challenge is identifying the most effective means to achieve that end.

We can assume the alternative scenarios as well:

Known End, Known Means: We know what we need to do and how to do it - a superior plan and the ability to execute that plan is a competitive advantage here.

Unknown End, Unknown Means: Exploration for the sake of exploration - this is where inventions like the microwave, penicillin, and velcro come from. Curiosity and accidents.

Unknown End, Known Means: High conviction that a particular set of means can be adapted to produce an asymmetric result - simple rules, unpredictable outcomes.

Known End, Unknown Means: We know the desired outcome or change in behavior, but the challenge is identifying the most effective means to achieve that end - experiment and iterate

Let’s throw this into a 2×2 (McKinsey, you’re more than welcome to steal this):

Goal-setting is an effective approach for the top two quadrants. This makes sense as they’re dependent on defining ‘known ends’, but is goal-setting as effective in the lower two quadrants?

We already gave a few examples of our ‘Explore’ quadrant here - more interactions increase the likelihood of happy accidents that come from our ‘Surface Area of Luck’ - whereby action over inaction produces some unexpected opportunity.

“You can increase your surface area for good luck by taking action.

The forager who explores widely will find lots of useless terrain, but is also more likely to stumble across a bountiful berry patch than the person who stays home.

Similarly, the person who works hard, pursues opportunity, and tries more things is more likely to stumble across a lucky break than the person who waits.”

Decision making in this context optimizes for action over inaction and serendipity. Given two similar choices, it asks which one produces a broader ‘luck surface area’.

That gives us:

Known End, Known Means → Execute → Plans & Targets: Decision making is proactive

Known End, Unknown Means → Experiment → Goal-setting: Decision making is reactive

Unknown End, Unknown Means → Explore → ‘Luck Surface Area’: Decision Making is chaotic and random

But what about ‘Unknown End, Known Means’? Decision making in this context is inherently emergent - more akin to sensemaking than optimization.

In this post, we’ll cover three perspectives on the challenges of goal-setting in radically uncertain environments.

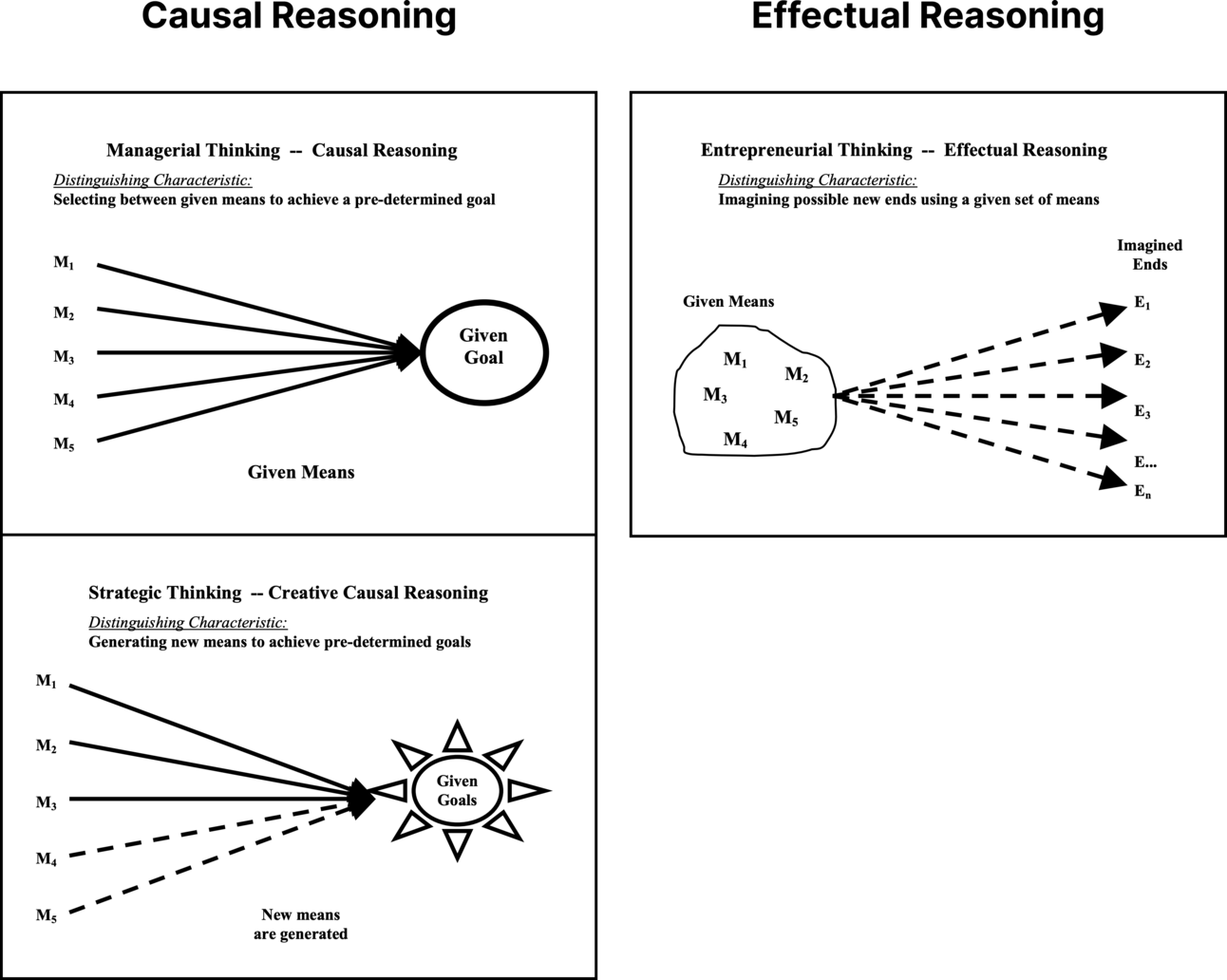

Causal rationality vs. effectual reasoning

The argument:

Starting with known ends (goal-setting) is effective for causal thinking - and for what Sarasvathy describes as ‘creative’ causal thinking, but may not be as effective in scenarios that require ‘effectual reasoning’.

A study done by Saras D. Sarasvathy at UVA titled, ‘What makes entrepreneurs entrepreneurial?’ explored the decision making of founders and proposes an interesting distinction between inherently exploratory (divergent) activities and ‘exploit’ (convergent) activities.

She explains this distinction as ‘Causal Rationality’ and ‘Effectual Reasoning’

“Causal rationality begins with a pre-determined goal and a given set of means and seeks to identify the optimal – fastest, cheapest, most efficient, etc. – alternative to achieve the given goal. A more interesting variation of causal reasoning involves the creation of additional alternatives to achieve the given goal. This form of creative causal reasoning is often used in strategic thinking.

Effectual reasoning, however, does not begin with a specific goal. Instead, it begins with a given set of means and allows goals to emerge contingently over time from the varied imagination and diverse aspirations of the founders and the people they interact with.

While causal thinkers are like great generals seeking to conquer fertile lands, effectual thinkers are like explorers setting out on voyages into uncharted waters.”

The argument here is that goals may be less effective in scenarios that call for effectual reasoning over causal reasoning (e.g. the ‘unknown end, known means’ quadrant).

The reality is that nothing emergent and explorative tracks progress towards a target (e.g. there’s no definition of ‘on track’ or ‘off track’ when there’s no known end), so we may need different ‘effectual’ techniques in this environment - techniques that don’t define success as an end, but measure the cohesion of means that have the potential to produce desired results.

The natural tendency is to want defined signals here - like a clear north star as a reference for progress, but in reality, we need something more like ‘scaffolding’ that guides decision making.

A startup in pursuit of product-market fit (PMF) is a compelling example of this ‘known means, unknown end’ quadrant because:

Competition is relative (goals tend to be absolute)

Adaptability matters more than optimization (survival > best)

To navigate decision making in this problem space, founders start and adapt with known means towards an unkown end. As Sarasvathy observed, these means are often their specific traits and abilities, unique expertise, their own network/distribution, and conviction in a narrative.

“Using these means, the entrepreneurs begin to imagine and implement possible effects that can be created with them. Most often, they start very small with the means that are closest at hand, and move almost directly into action without elaborate planning.

Unlike causal reasoning that comes to life through careful planning and subsequent execution, effectual reasoning lives and breathes execution. Plans are made and unmade and revised and recast through action and interaction with others on a daily basis. Yet at any given moment, there is always a meaningful picture that keeps the team together, a compelling story that brings in more stakeholders and a continuing journey that maps out uncharted territories.

Through their actions, the effectual entrepreneurs’ set of means and consequently the set of possible effects change and get reconfigured. Eventually, certain of the emerging effects coalesce into clearly achievable and desirable goals -- landmarks that point to a discernible path beginning to emerge in the wilderness.”

The explore-exploit dilemma, is something missing?

The argument:

The explore-exploit dilemma is often the framing for how goals support tradeoff decisions, but does this limit the learning/curiosity needed for this ‘adaptive’ quadrant?

The exploration-exploitation dilemma occurs in many of our own conscious and subconscious decision making functions - it’s also a widely referenced model for strategic decision making

We constantly balance the reward of known/unknown means and ends - but is this is an ‘optimization’ problem?

We often treat decisions around goals like the multi-armed bandit problem - allocating set resources between competing initiatives to maximize expected gain and as time passes, the value of those choices becomes better understood and we weigh alternatives.

But is this effective when we’re doing more sensemaking than optimizing?

Studies on the explore-exploit dilemma have tried to define what ‘explore’ and ‘exploit’ really mean and articulate the pitfalls on either side of the equation.

In the widely cited paper ‘The Interplay Between Exploration and Exploitation’, Gupta, Smith, & Shalley summarize different definitions of ‘explore’ and exploit’, but we could argue that the top half of our 2×2 aligns with ‘exploit’, and the bottom half aligns with ‘explore’.

And they frame the downsides on either side of the spectrum in a succinct and compelling way:

“Because of the broad dispersion in the range of possible outcomes, an exploration often leads to failure, which in turn promotes the search for even newer ideas and thus more exploration, thereby creating a ‘failure trap.’

In contrast, exploitation often leads to early success, which in turn reinforces further exploitation along the same trajectory, thereby creating a ‘success trap.’

In short, exploration often leads to more exploration and exploitation to more exploitation.”

Our fixation on pre-determined desired outcomes will likely lead us to predictable results (complacency in the success trap). Conversely, endless exploration has a hard time justifying investment when value is delayed and failure is the rule, not the exception - survivorship bias tends to have an impact here.

In entrepreneurial ventures, things like conviction help fill this gap - but we have a hard time finding a proxy for ‘effectual reasoning’ in mature organizations. The consequence of this is likely a decreased capacity for making ambitious bets.

“Objectives are well and good when they are sufficiently modest, but things get a lot more complicated when they’re more ambitious. In fact, objectives actually become obstacles towards more exciting achievements, like those involving discovery, creativity, invention, or innovation—or even achieving true happiness.

In other words (and here is the paradox), the greatest achievements become less likely when they are made objectives.

Not only that, but this paradox leads to a very strange conclusion—if the paradox is really true then the best way to achieve greatness, the truest path to “blue sky” discovery or to fulfill boundless ambition, is to have no objective at all.”

It’s easy to say that comfortability with uncertainty (unknown ends) presents asymmetric opportunities, but if goals are less effective, what’s the playbook for this adaptive environment?

The explore-exploit dilemma relies on a ‘reward’ as a primary driver for decision making, but a recent paper out of Carnegie Melon called ‘Embracing curiosity eliminates the exploration-exploitation dilemma’ proposes a focus on learning and ‘curiosity’.

The argument is that introducing information as a reward, or ‘learning for the sake of learning’ can outperform models that try to optimize the multi-armed bandit problem.

My background is in design and product management, not machine learning, but the compelling arguments for me were:

There is value in learning and curiosity with no defined end

There is a relationship between ‘explore’ and ‘exploit’ activities - though it’s inherently a tradeoff, each reinforces the other.

“Let’s consider colloquially how science and engineering can interact. Science is sometimes seen as an open-ended inquiry, whose goal is truth but whose practice is driven by learning progress, and engineering often seen as a specific target driven enterprise.

They each have their own pursuits, in other words, but they also learn from each other often in alternating iterations.

Their different objectives is what makes them such good long-term collaborators.”

Maybe the question here is what exactly is learning progress? And not ‘are we exploiting the right means to reach a desired end’, but progress towards learning for the sake of learning that ultimately reinforces exploitive strategic decisions.

Next week!

There’s still one more argument to explore here, which is ‘goal-induced blindness’. Next week we’ll dig into that along with a few models/frameworks that may complement goal-setting in these environments, for example:

Estruine Mapping

Wayfinding

Design Futures

Others? 👀 …let us know!

We hope this post was helpful and interesting! Have feedback? Just reply to this email! It would be great to get in touch!