Good morning! 🙂

In case you missed it, last week talked about how optical illusions help us think about biases, the dangers of confirmation bias, and how Amazon makes decisions.

This week:

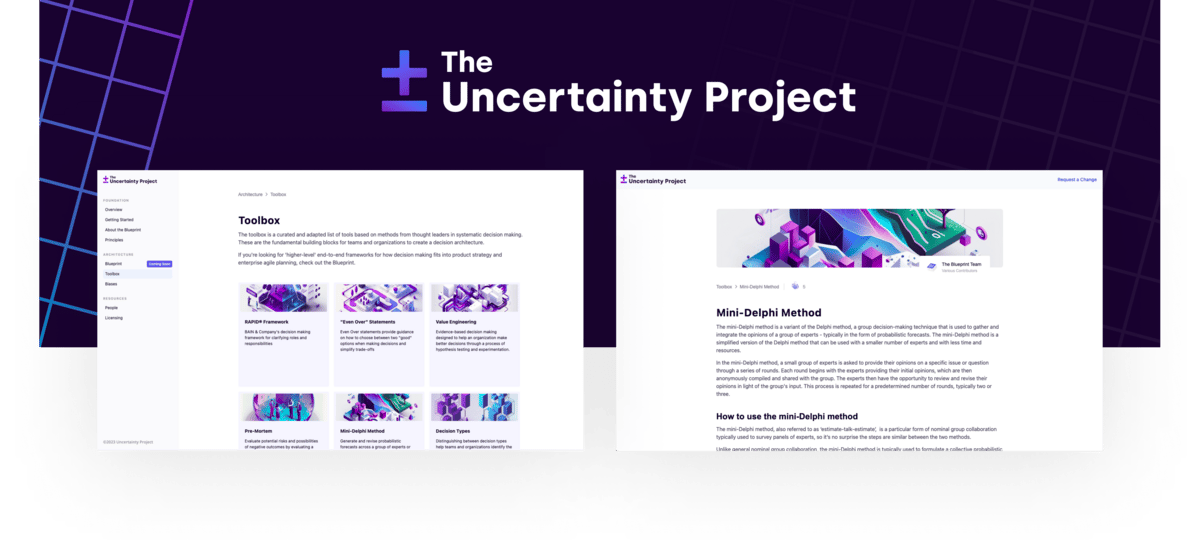

📣 Update! We’re rebranding!

🔮 Topic: Navigating uncertainty (and why we’re rebranding)

❌ Bias 7/50: Zero-Risk Bias

📈 Tool: Value Engineering

Update!

We’re weeks away from opening up the community!

We’ll be launching on March 6th and in preparation, we’re changing the name from ‘📘 The Blueprint’ to ‘🔮 The Uncertainty Project’ (More on that in a minute)

What you’ll find inside:

20+ tools and techniques for decision making

Overviews of 50+ cognitive biases

Conversations with other product leaders navigating uncertainty

Check out the all-new Uncertainty Project!

And we have a few other things in the works. We’ll be hosting workshops, interviewing product leaders, and publishing a playbook for group decision making.

In fact, if you’re interested in helping us test out ‘The Uncertainty Playbook’, please let us know here!

Why are we rebranding?

Well for one, it’s difficult to compete with Bryan Johnson (founder of Braintree that famously acquired Venmo) and his anti-aging science experiment.

More importantly, as we’ve spoken with many of you over the last couple of months about decision making, we wanted a name that better represented why we believe this is a worthy topic to explore.

How do we make decisions? What makes decision making effective?

Of course, there’s the consistency of monotonous decisions, but we’re interested in the mechanisms of strategic decision making - how do we take big swings? how do we handle risk?…

…How do we navigate uncertainty?

"Wherever you see a successful business, someone once made a courageous decision."

Developing great products happens in an environment of extreme uncertainty. We make decisions in scenarios where the information is incomplete (at best) and the outcome is unknown.

This is what we’re interested in exploring - navigating uncertainty. And though we’ll primarily cover strategic decision making in teams, the new name allows us to include other frameworks that may not be specific to decision making

What’s the meaning behind the symbol for the logo?

In mathematics, physics, and engineering, among other disciplines, the uncertainty or margin of error is denoted by the symbol: ±

Navigating uncertainty

Uncertainty is a difficult thing to manage. It’s uncomfortable to sit in. It’s visceral. The act of navigating uncertainty is unnatural and emotional. We can feel it. It causes anxiety and paralyzes many. Why?

We know that operating in this environment is unnatural by observing the effects of zero-risk bias, status quo bias, and risk/loss aversion. We tend to avoid jumping into the unknown or even reason our way into the illusion of certainty.

When processing information, we fall victim to the ambiguity effect, confirmation bias, and the bandwagon effect to find comfort in certainty, even when it’s misleading. We prioritize comfort over the best option.

These confounding variables create what Charlie Munger calls a Lollapalooza effect, which he describes as a “Confluence of psychological tendencies in favor of a particular outcome.” In this case, that outcome is complacency.

Munger uses the example of aviation to illustrate how combatting and manipulating these effects and their countereffects can have miraculous results. Uncertainty produces a web of confounding factors in decision making (much like gravity, air density, pressure, wind, and drag) that if mitigated and redirected can have explosive results.

The Uncertainty Project will focus on techniques for teams to navigate this cognitive minefield and combat the gravitational pull of complacency.

Uncertainty vs risk

Effectively navigating uncertainty is the exception, not the rule. In many organizations, this is often confused with managing risk instead of making the unknown, known and responding to new information.

Gerd Gerenzinger, who studies how we make decisions through uncertainty makes a clear distinction between risk and uncertainty. Risk can be calculated. With uncertainty, “calculation may help you to some degree, but there is no way to calculate the optimal situation.”

Gerenzinger argues that we have a natural rudder for navigating uncertainty - a collection of heuristics, our intuition, trust, and conviction.

Though many researchers disagree on the relative levels of impact certain tendencies have in different situations, behavioral economists agree on one thing: We must start from a place of humility and recognize the overwhelmingly complex forces at play when we make decisions - good or bad.

These cognitive functions exist for a reason, but more often than not, especially when recalling information, making predictions, interpreting probabilities, and responding rationally to risk, they work to our detriment.

“What makes a great decision is not that it has a great outcome. A great decision is the result of a good process, and that process must include an attempt to accurately represent our own state of knowledge. That state of knowledge, in turn, is some variation of ‘I’m not sure’”

Bias 7/50: Zero-Risk Bias

Zero-risk bias is a phenomenon in which individuals or groups tend to overestimate the likelihood and severity of rare or unlikely risks while underestimating the benefits or likelihood of more common or likely benefits.

This bias can lead to a preference for taking extreme measures to eliminate risk, even if the costs of those measures are outweighed by the potential benefits.

Zero-risk bias can even lead to group polarization, as individuals or groups tend to become more extreme in their views on risk as they discuss them with like-minded individuals. This can further reinforce the belief that extreme measures are necessary to address even small risks.

Zero-risk bias often leads to missed opportunities, as teams tend to shy away even from relatively minor risks, regardless of the relative potential outcome.

Tool: Value Engineering

This technique is adapted from the original author, Barry O’Reilly, best-selling author and co-founder of Nobody Studios. The original post can be found here

Value Engineering is a method for navigating uncertainty. It recognizes initiatives as experiments that create optionality and makes tradeoff decisions clear.

In an output-focused environment, backlogs of initiatives with heavy business cases often end up stack ranked and 'approved' with a set definition for their scope and expected value. This fails to create a necessary mechanism to shed what is not providing value and double down on promising initiatives. Therefore, losing bets fall victim to a self-reinforcing escalation of commitment and siphon resources from other, more opportunistic investments.

The Value Engineering approach recognizes these initiatives as a portfolio of bets and uses an evidence-based approach to make decisions as new information is revealed. This approach follows the cycle of hypothesizing a future outcome, making bets on what will drive that outcome, and making decisions to pivot, persevere, or stop:

Hypothesize: Quantify your beliefs of what value is, and how you will know it.

Bet: Test your hypothesis with experiments to gain knowledge to make better investment decisions.

Pivot and Persevere: Learn early and often at every level of the organization about what’s providing value and what’s not.

Adopting Value Engineering

Value Engineering is an evidence-based decision making model for identifying when to pivot, persevere, or stop investments. It requires teams to shift from a feature factory mindset towards an outcome-based, experimental mindset.

To avoid the escalation of commitment that naturally occurs with ongoing investments, we want to adjust for cost vs value over time. We already build this model implicitly in our heads for ongoing projects, but when we're in the middle of it, it's difficult to give appropriate weight to the warning signs. Visualizing this value vs effort model makes helps to see if the evidence supports the size of the bet.

Small bets create safe-to-fail experiments enabled by faster feedback loops, limited-risky investments, and keeping initiatives in a recoverable state by never being too big to fail.

Above all, the currency of Value Engineering is learning. It is a mindset shift at all levels that favors discovering the harsh realities over sticking to a plan that may be out of date from the moment you think it’s complete.

Getting Started

To start, we ask three questions:

What is the hypothesis?

How will we know when we've achieved the desired outcome?

What is the max 'bet' to achieve the desired outcome?

Simply put, we need to define the desired outcome, demonstrable measures or criteria that prove the hypothesis, and how much we'd be willing to pay for that outcome if we could buy it off the shelf.

We end up with a template for each initiative:

Hypothesis: We believe will result in . We will have the confidence to proceed when .

Desired outcome: Explanation of a future state, ideally measurable. This might be an OKR, a target for a KPI, or just an articulation of the future.

Max bet: If you could buy the outcome off the shelf, how much would you pay? This can be in terms of dollars, but it's often easier to define this as people over time (e.g. 2 teams over 16 weeks)

How this technique helps navigate uncertainty

Historically, in the traditional project portfolio environment, teams built heavy business cases with pipe dream ROI models to justify a locked-in budget over a long period of time. In today's outcome-driven environment, organizations have shifted focus to funding teams and outcomes over work.

Though this transition has been profoundly impactful, it's still difficult to have effective pivot/persevere conversations, especially with larger initiatives. The reality is that many initiatives continue to run through 'completion' and are judged on their results.

With one checkpoint, the only potential scenarios are luck or over-commitment. Introducing a framework for pivot/persevere decisions enables adjustment through uncertainty.

We hope this post was helpful and interesting! Have feedback? Just reply to this email! It would be great to get in touch!